“Declan Burke is his own genre. The Lammisters dazzles, beguiles and transcends. Virtuoso from start to finish.” – Eoin McNamee “This bourbon-smooth riot of jazz-age excess, high satire and Wodehouse flamboyance is a pitch-perfect bullseye of comic brilliance.” – Irish Independent Books of the Year 2019 “This rapid-fire novel deserves a place on any bookshelf that grants asylum to PG Wodehouse, Flann O’Brien or Kyril Bonfiglioli.” – Eoin Colfer, Guardian Best Books of the Year 2019 “The funniest book of the year.” – Sunday Independent “Declan Burke is one funny bastard. The Lammisters ... conducts a forensic analysis on the anatomy of a story.” – Liz Nugent “Burke’s exuberant prose takes centre stage … He plays with language like a jazz soloist stretching the boundaries of musical theory.” – Totally Dublin “A mega-meta smorgasbord of inventive language ... linguistic verve not just on every page but every line.” – Irish Times “Above all, The Lammisters gives the impression of a writer enjoying himself. And so, dear reader, should you.” – Sunday Times “A triumph of absurdity, which burlesques the literary canon from Shakespeare, Pope and Austen to Flann O’Brien … The Lammisters is very clever indeed.” – The Guardian

Monday, October 29, 2018

Event: Michael Connelly Interview at City Hall

The rest of the Murder One festival takes place next weekend, Friday 2nd to Sunday 4th of November, and features Lynda LaPlante, Liz Nugent, Peter James, William Ryan, Ali Land, Clare Mackintosh, Mark Billingham, Declan Hughes, Jane Casey and lots more. For details of how to book tickets to the events, clickety-click here …

Tuesday, September 18, 2018

Festival: Festival du Polar Irlandais Noire Emeraude

Wednesday 19 September, 7.30 pmFor all the details, clickety-click here …

OPENING EVENING

Benjamin Black (John Banville) in conversation with Clíona Ní Ríordáin

Born in Ireland in 1945, John Banville lives in Dublin. Since its inception, the work of this "goldsmith of words" has been rewarded with numerous literary prizes. Passionate about police literature of the 50s, he also wrote black novels under the pseudonym Benjamin Black, the last appeared Vengeance (2017); their recurring hero, coroner Quirke, was portrayed by Gabriel Byrne in a television series aired in 2014 on the BBC.

Thursday, September 20th, 7:30 pm

DETECTIVES AND CRIMINALS FROM PAGE TO SCREEN

Jo Spain in conversation with director Conor Horgan

The Irish novelist of crime fiction, Jo Spain, recently commissioned to write her first TV drama for RTÉ, will tell us about the difficulties of moving from writing novels to that of scenarios. Produced this summer by the directors of the hit Irish series Love / Hate, her Taken Down series is released on screen in November 2018.

Friday, September 21, 7:30 pm

SCENE OF THE CRIME

Alex Barclay and Declan Hughes in conversation with Declan Burke

Scene of the Crime will focus on Ireland as a backdrop for crime fiction and what is so revealed about contemporary society. Alex Barclay and Declan Hughes will also tell us about their experience when locating a plot in a foreign country, their motivations, the constraints that entails and the strengths that this narrative choice represents.

Saturday, September 22nd, 5pm

WHYDUNIT

Liz Nugent, Jane Casey and Declan Burke in conversation with Declan Hughes

Whydunit will examine the alternatives to the traditional black novel focusing in particular on the psychological drama as well as on the band police officer.

Liz Nugent, Jane Casey and Declan Burke will give us keys to understanding this form of crime novel that focuses more on the motivations of the character who committed a crime than on the murderer.

Saturday, September 22, 7:30 pm

TRUE CRIME

Eoin McNamee, Niamh O'Connor, Sam Bungey and Jennifer Forde in conversation with Wesley Hutchinson

Sam Bungey and Jennifer Forde are the creators of West Cork, a podcast produced by Audible, dealing with the murder of Frenchwoman Sophie Toscan de Plantier in the West Cork area. With Niamh O'Connor and Eoin McNamee, they will discuss the ethics of novel based on a real news story.

Wednesday, November 15, 2017

Wednesday, July 26, 2017

Tuesday, October 11, 2016

Event: TROUBLE IS OUR BUSINESS at the Red Line Festival

TROUBLE IS OUR BUSINESS

An Evening With Ireland’s Finest Crime Writers

Join us for an evening of discussion on Irish crime writing with some of

Ireland’s best crime writers. Author, editor and journalist Declan Burke

will be leading the conversation with Alan Glynn, Declan Hughes and

Alex Barclay to discuss the ins and outs of the crime-writing process, the development of gripping plots and characters, as well as the past and present of Irish crime writing. Perfect for crime fiction fans and aspiring authors, it’s sure to be a wonderful evening! In association with New Island Books.

Date: Wednesday 12th October

Time: 8pm

Venue: Civic Theatre, Tallaght, Dublin 24

Price: €8/€6

BOOK NOW

Event: Declan Hughes and Alan Glynn on Raymond Chandler

At the 15th annual Imagine Arts festival in Waterford this October, Irish crime writers Alan Glynn and Declan Hughes will read from their work and discuss the influence of Raymond Chandler on their writing and on contemporary crime fiction. This event will take place in partnership with the Irish Writers Centre as the Imagine Festival commemorates the memory of Raymond Chandler and his close connection with Waterford.This free event takes place at Waterford’s St Patrick’s Gateway Centre on October 23rd. For all the details, clickety-click here …

Monday, September 12, 2016

Launch: THE CONTEMPORARY IRISH DETECTIVE NOVEL

Irish detective fiction has enjoyed an international readership for over a decade, appearing on best-seller lists across the globe. But its breadth of hard-boiled and amateur detectives, historical fiction, and police procedurals has remained somewhat marginalized in academic scholarship.For more, clickety-click here …

Exploring the work of some of its leading writers, The Contemporary Irish Detective Novel, edited by Elizabeth Mannion, opens new ground in Irish literary criticism and genre studies. It considers the detective genre’s position in Irish Studies and the standing of Irish authors within the detective novel tradition.

Writers John Connolly, Declan Hughes, and Stuart Neville will participate and will be signing books, as will Professors Elizabeth Mannion, Fiona Coffey, and Brian Cliff.

Tuesday, September 13, 7:00 p.m.

at Glucksman Ireland House NYU

Friday, July 22, 2016

Books: THE CONTEMPORARY IRISH DETECTIVE NOVEL, ed. Elizabeth Mannion

Irish detective fiction has enjoyed an international readership for over a decade, appearing on best-seller lists across the globe. But its breadth of hard-boiled and amateur detectives, historical fiction, and police procedurals has remained somewhat marginalized in academic scholarship. Exploring the work of some of its leading writers―including Peter Tremayne, John Connolly, Declan Hughes, Ken Bruen, Brian McGilloway, Stuart Neville, Tana French, Jane Casey, and Benjamin Black―The Contemporary Irish Detective Novel opens new ground in Irish literary criticism and genre studies. It considers the detective genre’s position in Irish Studies and the standing of Irish authors within the detective novel tradition. Contributors: Carol Baraniuk, Nancy Marck Cantwell, Brian Cliff, Fiona Coffey, Charlotte J. Headrick, Andrew Kincaid, Audrey McNamara, and Shirley Peterson.For all the details, clickety-click here …

Sunday, January 10, 2016

Essay: ‘Contradictions in the Irish Hardboiled: Detective Fiction’s Uneasy Portrayal of a New Ireland’

‘Contradictions in the Irish Hardboiled: Detective Fiction’s Uneasy Portrayal of a New Ireland’ by Maureen T. Reddy

The sheer size of the recent boom in Irish crime fiction has tended to obscure its most striking feature: a striking lack of diversity, in terms of subgenres and models. Virtually all twenty-first-century Irish crime fiction is derived from the tradition of the American hardboiled, yet few reviewers or scholars have addressed the thoroughgoing similarity of literary descent, beyond noting that much Irish crime fiction is “noirish.” Current Irish crime writers tend to see themselves as connected to the American hardboiled tradition, judging from published interviews, blogs, and even titles of collections—for example, Down These Green Streets (2011) and Dublin Noir (2006). Many of the twenty-first-century Irish series feature either tough-guy private eyes or police detectives whose style of speech, loner tendencies, and cynical attitudes link them more closely with the conventions of hardboiled than with the police procedural. Other subgenres—cozy mystery, academic mystery, legal fiction, spy, and comic or “caper,” for instance—have found few new Irish practitioners, although all of these specialties remain popular with both readers and with non-Irish writers. Although not a new form per se, the Irish hardboiled represents a significant development in Irish literature through its resurrection of an established literary form not previously associated with Irish writers. That it arose when the definition of Irishness itself was newly and widely under interrogation is no coincidence.

Most traditional definitions of Irishness were obsolete by the early 2000s. They were unsettled by many developments: successive public scandals (political, economic, and religious, beginning in the 1990s), the country’s membership in the European Union, immigration after a long history of emigration, and the economic boom and then bust, along with widespread access to global media and increasing levels of education among the populace. But the obsolete markers of Irishness were not replaced with a coherent ideology. Instead, the question of Irishness has in many ways been left up for grabs.

Recent Irish crime writers have been deeply interested in working through the problem of redefining Irishness. This problem has been raised also in much contemporary Irish non-genre fiction, but the hardboiled form that has profoundly influenced so many contemporary crime writers works against a progressive or liberatory conception of Irishness. The intensely conservative ideology expressed in the form of much of this Irish writing is at odds with its more progressive content; sometimes, the authors find themselves writing into dead ends from which series cannot extricate themselves.

In The Dragon Tattoo and its Long Tail (2012), a survey of contemporary European crime fiction, David Geherin describes Galway’s Ken Bruen as an exception to the general rule that “European crime writers deliberately try to distance themselves from their American counterparts.” That claim is simply false unless one excludes all Irish crime writers from consideration; Irish writers of hard-boiled fiction, and not just Bruen, are at pains to claim a connection with their American counterparts and, more important, with their American literary forebears. They do so by drawing direct attention to them in their novels and modeling plots on theirs. Declan Burke, for instance, has frequently mentioned—on his blog, in interviews, and in his introduction to the Books to Die For (2012) collection—that his main influence is Raymond Chandler. In the third episode of RTÉ’s “Irish Noir” radio series in 2013, Burke said that he was inspired to write crime fiction by Chandler; Burke “wanted to take the classic tropes of 1930s stuff” and put them in Ireland.

Similarly, Declan Hughes’s author’s web page lists “Ten Crime Novels You Must Read Before You Die,” which has Dashiell Hammett’s The Glass Key as number one (with mentions also of The Maltese Falcon and Red Harvest) and Raymond Chandler’s The Long Goodbye as number two (followed by mentions of The Big Sleep and Farewell, My Lovely). Hughes describes Hammett as “The Master—the JS Bach, the Louis Armstrong of crime fiction” and Chandler as “The greatest prose stylist in the genre. Romantic, lyrical and witty.” Even the title of the first collection of Irish crime writing and writing about Irish crime writing, Down These Green Streets, is a tribute to Chandler. Andrew Kincaid rightly notes that “the most striking aspect of many of these [Irish noir] novels is the conscious reference to American noir.”

The American hardboiled is rife with contradictions: the outsider detective who on closer examination turns out to be a social insider; complicated attitudes toward the police (they are definitely stupid, possibly corrupt, but the detective works with them anyhow); and depictions of women, who are both the major threats to the detective and those he is dedicated to protecting. The Irish version of the genre compounds the contradictions. The Irish protagonists frequently criticize the Americanization of Ireland, from attitudes to accents, and yet they do so in the context of an American literary form in which the characters hold an American position.

Although the fictional Irish private eyes resemble Hammett’s and Chandler’s solo professional detectives in their cynical attitudes and tough style of speech, their backstories offer a major difference—indeed, that they have backstories at all is a departure from the original formula. In the American hardboiled, the detectives are loners by choice and are depicted as free, a condition all the more attractive given the novels’ portrayals of most family relationships as poisonous. In contrast, the detectives in Irish novels are not so much free as they are miserably lonely; they are decidedly unfree, because permanently damaged by their own toxic family relationships.

This departure from the conventions of the American hardboiled reflects Irish historical circumstances, and draws attention to the fundamental changes in the Irish national story that are central to the new Irish crime fiction. The lone male—the cowboy, the explorer, the one who lights out for the territory, leaving a feminized civilization behind—is an essential, heroic figure in American nation-building mythology. American hardboiled detectives are drenched in this mythology. In Irish cultural traditions, the solitary male figure is generally both unusual and pitiable. The lone male who stays in Ireland is a sad figure in popular culture, epitomized by the lonely bachelor on a farm. The most common association in Irish history with solitary males, however, is with emigration, evoking the thousands who left family and country behind, not fully by choice. The territory for which these men lit out was not open and liberating, but colonial and stifling.

While it is true that the figure of the exile has complicated that picture in Irish literature at least since Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist, that exile is of course always in another country, not Ireland itself. The most Irish Irishman is rural, settled, and as the constitution asserts, fully embedded in a family. These claims both reflect and reinforce social norms that prevailed for decades in Ireland. The hardboiled loners, with their miserable family histories, draw attention to a part of the story usually left out of the national mythology: that the Irish family may be “the necessary basis of social order” while at the same time being the locus of abuse, oppression, and misery. Perhaps, then, that social order is of a piece with its basis—abusive, oppressive, miserable, and dangerous—and therefore disruptions in it are in fact desirable, leading to a greater social good than would its restoration.

The American hardboiled usually suggests something along these lines regarding about the ruling classes—one of many ways that the form is distinct from the British golden age mystery, in which the detective acts to restore order and can therefore be seen as an agent of the ruling classes. However, the American hardboiled detective consistently labors to restore two elements of the existing social order—restrictive gender and race roles—which complicates his supposed independence from the ruling classes and makes him complicit in their hegemony, a fact that the novels work hard to obscure.

Late twentieth-century American feminist writers and writers of color—for example, Sara Paretsky, Marcia Muller, and Walter Mosley—have sought to intervene in the received trope of the hardboiled detective, revising both the solitariness and the class loyalties of the hardboiled detective. Their interventions cast further light on the Irish versions. In American feminist series featuring female detectives, the authors generally provide the detective with a backstory that explains her solitariness and that shows her creating a chosen family, outside the usual confines of the patriarchal nuclear family. A number of writers of color take this revision further by creating detectives who are extensively connected with their communities and who even often have primary responsibility for children, theirs by birth or adoption. Such revisions serve to highlight hardboiled ideology’s valorization of whiteness and masculinity while also calling into question received ideas about autonomy and freedom. In the Irish case, however, the revision does not challenge hardboiled ideology so much as it disputes the veracity of official Irish ideology. The detectives’ lives strongly suggest both that the family is the basis of a social order that has gone seriously wrong, and that the family unit itself is often far more damaging and dangerous than the official Irish story could ever admit. And yet, the Irish detectives long for family stability and regret their own solitariness, which imbues the five series discussed here with a peculiar nostalgia—one that consistently subverts their critiques of the Ireland now passing into history.

A case in point is Hugo Hamilton’s truncated Pat Coyne series, which technically does not fit the private eye model, as Coyne is a member of Garda Síochána in the first book. But his status as a garda is incidental to the novels’ plots, in which Coyne essentially functions as a private eye. Hamilton’s Headbanger (1996) was the first Irish hardboiled novels; in it, Coyne imagines himself as protecting all and stopping crime though he is not very good at either task. Coyne has a number of obsessions, but “above all else, he was concerned with extinction; the disappearance of legendary people. Last men belonging to ancient and pure civilizations which had clashed with modernity. Men and women like the Blasket Islanders.” At one point, he thinks of his father, who moved to Dublin from West Cork “to claim his part in the making of a new Ireland.” (H34) Coyne sees the country changing again, and thinks that “all the new historical landmarks would be eclipsed by new outrageous shrines of crime”, (H34) mentioning a pedophile priest at a summer camp in Glendalough: “The sacred places of Irish history defiled by new atrocities” (H 34).

The novel focuses on Coyne’s determination to bring down Berti “Drummer” Cunningham, a gangster, murderer, pimp, and drug dealer who has opened a nightclub and “was now transforming himself into a regular statesman” (H 70). This novel’s explicit concern with the “new Ireland” and the destruction of traditional Irishness corresponds very closely to American hardboiled fiction’s concerns about the “new” United States and loss of whiteness in the 1920s and 1930s seen in, for example, Dashiell Hammett’s “The House in Turk Street” and Raymond Chandler’s “Finger Man.” Pat Coyne is treated ironically in many ways, unlike the original hardboiled detectives, but the concern about social changes is handled entirely without irony: the novel repeatedly demonstrates that Pat is right to be worried. The threats to Irishness in this novel come not from the outside, but from traditional centers of authority: the corrupt hierarchy of the gardaí that allows Berti and his ilk to flourish, the church that shelters pedophiles, the ordinary Irish people who value money above traditional culture. Headbanger suggests that Ireland is fast becoming the fifty-first American state, and even a hard man like Coyne cannot stop the process.

The second Coyne novel, Sad Bastard (1998), ratchets all these concerns up and places an immigration scam at the center of the plot. Many characters in the novel complain about immigrants—especially Eastern Europeans—but Coyne welcomes them, seeing them as returnees: “These were the Blasket Islanders coming back. The tide of emigration was turning. Here they were, the first of them—thousands who had fled poverty and were now returning at last.” But the reality is that they are not “returnees.” Coyne’s insistence on mistaking them in this way is ominous. His superficial openness to others, in fact, covers precisely the opposite: he does not welcome new people or a new Ireland, but wants a return to an old Ireland and to “authentic” Irishness. Coyne’s sentimentality regarding immigrants to Ireland stems from his fury with the “new” Ireland. In a shop on Grafton Street, he wonders, “What evolutionary platform had the Irish arrived at now. . . . Their identity was what they purchased. All around him tills were ringing, credit cards sliding, people making choices with great conviction” (SB 54). At the end of the novel, when the thugs have been sorted by Coyne, acting alone, he reflects that,

Maybe Ireland was not a real place at all but a country that existed only in the imagination. In the songs of emigrants. In the way people looked back from faraway places like Boston and Springfield, Massachusetts. Maybe it was just an aspiration. A place where stones and rocks had names and stories. Maybe this was the glorious end. The end of Ireland (SB 189–90).Of course Coyne is right in thinking that Ireland—like all nations—exists only in the imagination, but his ultimate resignation to the disappearance of his imaginary country, and his sentimentality, set him apart both from earlier tough-guy detectives and also from those of the hardboiled counter-traditions. Like the original hardboiled detectives, Coyne is positioned as an outsider and an independent thinker, at odds with most forms of authority. But the reality is that he is a social insider by virtue of gender, sexuality, and nationality. Also akin to those earlier detectives, Coyne is willing to engage in violence—even extreme violence—and is the only fully trustworthy character in the novels. In contrast to the hardboiled detectives of the counter-traditions, Coyne is nostalgic for a past that was, in fact, oppressive to many. It is not clear why Hamilton chose not to continue with the Pat Coyne series, but these two novels suggest a dead end: a hardboiled protagonist who is treated ironically, yet whose deeply conservative impulses we are meant to respect, with an embedded social critique that is also a plea for a return to an imaginary prelapsarian past. There is no place to go from there.

These two novels serve as prequels, of a sort, to Irish noir—much of which, like Hamilton’s novels, only slightly adapts the conventions of the hardboiled tradition, offering a recapitulated version of the dominant discourse, as if the developments in the hardboiled in the last part of the twentieth century had never happened. Ken Bruen’s Jack Taylor, Declan Hughes’s Ed Loy, and Declan Burke’s Harry Rigby are hard-drinking, and sometimes hard-drugging, tough guys who follow their own codes, determined to resist the Americanization of Ireland and to expose corruption among the powerful. Yet each one of these series reaches the kind of dead end that we see in Hamilton’s second book. Only Bruen has succeeded in writing past it, continuing his Jack Taylor series beyond Sanctuary (2010), a novel in which form and content engage in what reads like a final clash.

The best-known of the contemporary Irish crime writers is Benjamin Black, the pen name of John Banville. His use of unrevised hardboiled conventions is persisting and unmistakable. His Quirke series—set about fifty years ago, and begun with Christine Falls, published in 2006—offers the innovation of a doctor (a pathologist named Quirke) as the central consciousness of the novels, but otherwise directly incorporates hardboiled conventions and is fully immersed in hardboiled ideology. Quirke, flawed as he undoubtedly is, the sole trustworthy character. Other of Banville’s novels, such as The Book of Evidence (1989), which was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize, and Athena (1995), often focus on crime, and are both thematically and stylistically closely related to his work as Benjamin Black. However, the author insists that the Black novels differ from the Banville books; he describes the former as “cheap fiction” that he writes very quickly, in contrast to the novels he publishes under his own name—an assertion that infuriates other crime writers. Black adopts, entirely uncritically, the whole of hardboiled ideology, structure, and tropes; his embrace of a bygone tradition also explains why the novels are set in the 1950s instead of in a more contemporary period. The Quirke series is suffused with beliefs and attitudes, particularly regarding women, that would seem anachronistic in the twenty-first century. James Naremore has described the characteristic tough, cool voice of the hardboiled detective as the “Voice of Male Experience.” It might be more specifically identified as the voice of heterosexual, white, male American experience. Black’s Quirke is the voice of white, male, heterosexual, settled Irish experience in a period in which those terms equated with Irishness itself. Although those terms no longer suffice to describe Irishness, the Quirke series labors to reinstate only slightly revised versions of them.

All the novels in the Quirke series revolve around the deep corruption of powerful Irish institutions. The alternative these novels offer to that corruption is a pseudo-outsider status embodied by Quirke that is presented as a more authentic version of Irishness than the Irishness that enabled such corruption in the first place. Maleness, whiteness, and heterosexuality are never interrogated in Black’s novels (nor in the American hardboiled). Quirke’s villains are those who pervert those categories—such as the child-molesting priest Fr. Honan in the sixth Quirke novel, Holy Orders (2013)—but the categories themselves are left unquestioned. The multiracial realities of contemporary Dublin are largely excluded from these novels, which are set in the past, before much immigration to Ireland. However, Holy Orders includes Traveller characters who appear in an entirely stereotypical way. The Travellers function much as the Asian characters operate in the American hardboiled: as mysterious, dangerous, unknowable, frightening Others who must be contained. Most dangerous of all is a Traveller woman whom Quirke finds deeply alluring. Holy Orders’s treatment of women parallels that of Hammett’s and Chandler; women appear as deadly threats to the detective, and by extension, to all of society.

Unsurprisingly, then, instead of writing a seventh novel featuring Quirke, Black next produced a new work featuring Philip Marlowe, Chandler’s detective: The Black-Eyed Blonde (2014). The Black-Eyed Blonde is a logical step in Black’s dalliance with the hardboiled. From the start, Quirke has been as close to Marlowe as a character could be without actually being Marlowe. As many of the novels he has written as John Banville thoroughly critique some aspects of the past—the stranglehold of the church and of the rich on the rest of the nation, in particular, and the seemingly limitless government corruption that enables the powerful to do as they please—the lack of critique of the rigid gender roles of 1950s Ireland in his detective fiction is especially notable. Indeed, the Black novels are suffused with nostalgia for the womanly women and manly men of the 1950s.

One question raised by the boom in Irish detective fiction is the very question of whether the investigators have any basis in reality. The hardboiled novel depends on at least a surface verisimilitude. Readers have to be willing to believe that there are private detectives at work in Ireland for the fictional detectives to gain our trust. Oddly enough, although there is certainly disposable income available to pay private detectives in Ireland, even post-bust, there is little public acknowledgment that such detectives work in the country.

Early in his first Jack Taylor novel, The Guards (2001), Ken Bruen has his narrator protagonist explain that he is not actually a private investigator: “There are no private eyes in Ireland. The Irish wouldn’t wear it. The concept brushes perilously close to the hated ‘informer.’ You can get away with most anything except ‘telling’.” That widely shared view of the informer is sharply challenged by a character in another hardboiled novel. Declan Hughes has an Irish journalist comment bitterly on the influence of the Catholic church in pre-Celtic Tiger Ireland, describing doctors as “The Church’s willing enforcers” and going on to claim that “If Ireland had been in the Eastern bloc, we would have been riddled with secret police. We’d’ve had more police than people. I love this thing that we’re supposed to hate informers, of all things, Jesus, we’d give up our own children so long as we could do it in secret.” Although Bruen’s Jack Taylor goes on to function as a professional private eye, taking payment for that work, he continues to insist to potential clients that he is not one. Of the four Irish hardboiled detectives, only one actually calls himself a detective: Declan Hughes’s Ed Loy, who became a professional private investigator during his nineteen years in the United States The others describe themselves variously as a “research consultant,” in the case of Declan Burke’s Harry Rigby, a “finder,” in the case of Ken Bruen’s Jack Taylor, or define themselves primarily in terms of a different job, such as Quirke, a pathologist, or a former job, such as Pat Coyne, who has been dismissed from the gardaí. In contrast, the fictional American private eyes that serve as models for the contemporary Irish ones insist on their professional-

ism. They often mention their credentials in the course of their narratives, and they define themselves almost entirely by their jobs. Indeed, Dashiell Hammett’s character the Continental Op is so closely identified with the job that he remains nameless throughout the series.

Hughes’s Ed Loy, the sole Irish hardboiled protagonist to think of himself as a private investigator, sounds a lot like Hammett’s Op when a client tries to fire him in The Wrong Kind of Blood (2006). He responds by defining the P.I.:

He’s too shabby and disreputable and hustle-a-buck ordinary to make the grade at your charity balls and grand-a-plate dinners, and that suits him fine, because that way, he can get on with what he’s been hired to do. That’s the only point of him really, like a dog that’s been bred to work, he can’t relax by sitting around. He’s got to be prying and poking and stirring things up until somehow, out falls the truth, or enough of it to make a difference.Later, a police investigator named Geraghty from the National Bureau of Criminal Investigation repeatedly challenges Ed about his right to work in Ireland because he is not licensed there (as a matter of fact, Ireland has no licensing system for investigators). Geraghty mocks the very idea of a private eye by using the clichés of the hardboiled genre: “A private dick, is it? Fast cars and bourbon chasers and a forty-five, what? Is that the way it is, Ed, shoot-outs and double-crosses and dames?” (WKB 231). Geraghty is crude and unsympathetic, but his straight-from-the-pages-of-American-fiction description of Ed’s life is not far off as a summary of The Wrong Kind of Blood.

Each of Declan Hughes’s first four Ed Loy books roots its plot in a ripped-

from-the-headlines issue of Celtic Tiger Ireland: property development illegalities in The Wrong Kind of Blood, child sexual abuse and human trafficking in The Color of Blood, abuse in the industrial schools in The Dying Breed (2008) (published in the United States as The Price of Blood), and gangland activity by former paramilitaries in All the Dead Voices (2009). The fifth—and thus far, the last—Loy novel, City of Lost Girls (2010), links Los Angeles and Dublin through a psychopathic serial killer involved in the film industry.

Hughes seems to have deliberately chosen the American hardboiled for the style of his crime novels, with Hammett and Chandler his literary models. Even his detective’s name—a loy is a long, narrow spade used in Ireland, perhaps most famously as the putative murder instrument in Synge’s Playboy—seems a nod to Hammett’s Sam Spade of The Maltese Falcon (1930). The second Loy novel, The Color of Blood, is an extended riff on Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep: it features a wealthy, deeply troubled family in which the patriarch—now dead, in the Hughes novel—is extremely powerful; spectacularly damaged adult children; a mentally ill character who acts out violently; a plot that turns on blackmail through pornographic photographs; connections with a crime syndicate; a helpful cop who is frustrated by his (possibly crooked) superiors and also by the detective’s behavior, and so on. The most direct reference to Chandler, though, is in Ed Loy’s extended descriptions of the Howard family home, which in many particulars, such as faux-medieval stained glass, strongly resembles Sternwood’s house in The Big Sleep. Rowan House, Loy tells us, “looked like a Victorian merchant’s idea of a baronial castle” (CB 63).

In common with earlier hardboiled writers, Hughes devises plots that repeatedly demonstrate the close connections between the wealthy and powerful and the criminal underclass. In his novels, the wealthy are willing to do anything, including kill their own children, to hold onto their money, power, and cherished respectability. The Ed Loy novels, like their American hardboiled antecedents, insist on the utter corruption of the official power structure. The detective stands alone against that corruption, and endures as well as metes out tremendous violence—and always loses in the end. Or to be more precise, he generally solves the cases on which he is working, but the criminals are not brought to justice, nor is there a sense that Ed’s intervention has made any lasting difference in straightening out the crookedness of the world. Like Chandler’s Philip Marlowe, Ed is a romantic, a knight errant to whom his cases are more than jobs. When a client turns out to be unworthy of Ed’s services, Loy chooses his own idea of justice over completing his work. As he says in the opening sentence of the second novel, “The last case I worked, I found a sixteen-year-old girl for her father; when she told me what he had done to her, I let her stay lost” (CB 3).

Also like Hammett’s and Chandler’s detectives, Ed Loy is essentially a loner. Hughes, unlike his American models, sketches in his background to explain that solitariness: his father disappeared when Ed was a teen (Ed finds out in the first novel that the father was murdered) and Ed caught his mother with another man. Ed, we are told, went to the United States and did not return to Ireland until after his mother’s death. In the first novel, he is back in Dublin for his mother’s funeral but fully intends to return to California—significantly, Hammett and Chandler territory—which he thinks of as a place that lets one start over, “be whoever you wanted to be,” unlike Dublin, “where everyone was someone’s brother or cousin or ex-girlfriend and no one would give you a straight answer, where my da knew your da and yours knew mine, where the past was always waiting around the next corner to ambush you” (WKB 115). Complicating this view of California is the fact that he has left behind there an ex-wife whom he still loves, and with whom he suffered through the death of their small daughter—although Ed learned he was not her biological father when a transfusion was needed and his wife said his blood would not be a match. Loy can no longer in fact be “whoever [he] wanted to be” in either Dublin or California.

Like Ed Loy, none of the other protagonists in these Irish hardboiled novels is entirely separate from family entanglements—although each is a loner, either by temperament or circumstances, or else distanced from his family in opposition to his own desires. Hamilton’s Pat Coyne desperately wants to be a regular family man and even sees himself as a “father figure to the city of Dublin” (H 1), but he does not understand his wife, Carmen. By the start of the second novel, Sad Bastard, they are separated, with their two daughters living with Carmen in the family house and Coyne living with his son, Jimmy—a drug-using petty criminal—in a depressing flat. Declan Burke’s Harry Rigby’s parents are dead; his brother Gonzo is a psychopathic criminal who Harry ends up shooting in Eight Ball Boogie (2003) to protect his son, who is actually that brother’s son by Harry’s wife and Gonzo’s ex-girlfriend. Bruen’s Jack Taylor frequently thinks about his dead father, who like Jack himself was the target of Jack’s deeply cruel, deeply pious mother’s endless wrath. As Bruen’s series opens Jack and his mother are estranged, with the mother appearing every once in a while to castigate Jack or sending her emissary, the local parish priest, to do so for her. She dies in one of the early novels unmourned by Jack. Jack is briefly married during the course of the series, but that marriage, and every other romantic relationship he has, is eventually destroyed by his drinking and drug use. Benjamin Black’s Quirke has an exceptionally complicated set of family relationships: an adoptive father who rescued him from a nightmarish orphanage and then evidently favored him above his biological son; an impossible, enduring love for that adoptive brother’s wife; and a biological daughter who has been raised by her uncle to think that Quirke is her uncle.

Quirke was married but his wife—the sister of the woman he really loves—died. Unsurprisingly, his romantic relationships, too, tend to be limited and ultimately unhappy. Quirke’s work as a pathologist seems chosen to fit with his personality: he is more comfortable with the dead and with silence than he is with most relationships with living human beings. This litany of damage and loss in the lives of the Irish detectives is one of the subgenre’s most notable departures from the model of American hardboiled, in which the protagonists tend to be atomized and immune to human involvement—although the end point may be similar, with solitary detectives alienated from most ordinary human relationships.

The detectives’ own family situations, troubled as they are, are frequently less disastrous than those they encounter during the course of their investigations. The few intact families the novels include are usually held together by lies and secrets or bound to each other by violence and criminality, or both. For instance, Ed Loy’s chief nemeses in Hughes’s series are gangster brothers, the Halligans, who are both terrifyingly violent and deeply loyal to each other. In the pantheon of disturbed and disturbing families in the Irish hardboiled, one of the most intriguing is the Hamilton family in Declan Burke’s second Harry Rigby book, Slaughter’s Hound (2012). The upper-class Hamilton family includes Harry’s friend Finn, Finn’s adoptive mother, and his now-dead adoptive father, as well as a young woman who believes herself to be Finn’s also-adopted sister but is in fact his child with his mother. As an adolescent, Finn supposedly witnessed his father’s suicide but we learn that Finn actually murdered him. Finn and his mother’s ex-lover are involved in a scam in which they copy original paintings and then sell both the copy and the original. Their criminal enterprise creates an even tighter bond than their familial relationships. That tangled family story is only slightly messier than Harry’s own; significantly, he and Finn met when they shared a cell in a hospital for the criminally insane, to which Harry was remanded after killing his brother at the end of the first Rigby book, Eight Ball Boogie.

Burke cleaves closely to his American models in several ways. Harry’s narration of the two novels, for instance, evokes the spare, cool, ironic, self-deprecating voice of Chandler’s Marlowe novels, most directly when Harry reminds us of his injuries while downplaying them, as in this moment from Eight Ball Boogie:

I dug the Maalox out of my pocket, poured the contents down a drain, threw the empty bottle into the river. I was going to need all the pain I could get, just to keep me sane. The bottle bobbed away towards the bend and the bridge, heading for the open sea. I bade it bon voyage and told it to watch out for icebergs.Burke takes no chance that we might we miss Harry’s connection to his American predecessors. Harry evokes them directly several times, as when he describes a thug as looking “like Bogey spoofing on Edward G. Robinson” (EBB 246). Most jarring in twenty-first century novels are Harry’s extremely biased attitudes toward women and gay men, attitudes that the novels’ plots reinforce by positioning women and gay men as major threats to society. In the Rigby books, all women are dangerous, either directly (a property developer’s wife, Helen Conway, in Eight Ball Boogie, turns out to be the head of a criminal enterprise) or through their sexual appeal, as was the case with Harry’s wife—which leads men into trouble, as in the American hardboiled tradition of the spiderwoman. The most prominent gay character in the Rigby novels is Detective-Inspector Galway, who Harry variously describes as a “fruit” (EBB 100), a “pederast” (EBB 226), “the fag” (EBB 226, 227), and “the fairy” (EBB 270). When Harry first sees Galway—and well before he knows Galway is crooked—he describes him as “dapper” and concludes, “he was a fruit, a banana, bent for sure but so yellow about it people didn’t really notice” (EBB 100). That the “bent” guard turns out to be “a cop bent all ways up” (EBB 233) implies that Harry’s prejudice against gay men is rooted in some kind of truth, that they are major threats to social order.

Notable, too, is Harry’s use of “yellow” to describe Galway’s gayness, as it calls to mind the “Yellow Peril” discourse that so many of Dashiell Hammett’s Continental Op stories call upon, in which the “yellow” character is the brains behind a criminal enterprise and is often also described as not heterosexual, somehow less “masculine” than the white detective. This use of sexist, racist, and heterosexist patterns from the American hardboiled in Irish novels written nearly a century later not only ties the contemporary novels to their models, but also limits their critique of twenty-first-century Irish social problems, by suggesting that the solution would be a return to a time when women and gay men stayed in their subordinate places. And yet, the logic breaks down quickly. It is precisely those old social roles and systems of power that led to the social and political mess that the Rigby novels tackle.

In Burke’s novels, all members of the official criminal justice system are crooked, no one can be trusted, and no one is safe. The moral bankruptcy of the old authorities is abetted by the general public’s lack of interest in setting things right. The politician at the center of the property scandal Harry exposes during the course of Eight Ball Boogie will probably suffer no damage to his image or career. He may not be re-elected, but he has a bright future in corporate directorships. Even Brady, the guard in Eight Ball Boogie with whom Harry eventually collaborates to catch Galway, the crooked cop who for many years has been stealing drugs and selling them, is motivated less by a righteous commitment to justice than he is by his own aggrieved sense that he should be making more money and enjoying a higher rank. Brady is interested in exposing Galway primarily because Galway stands in the way of his own promotion. Further, Brady is willing to subvert the law in order to get what he wants; he does not participate in the drug ring, but he does falsify evidence, including planting a gun on Galway and making sure it carries Galway’s fingerprints instead of Harry’s. Brady’s bitterness about the sorry state of Irish society and the bankruptcy of traditional authority is meant to explain his disregard for the law; he feels justified in using any tactic to bring down the bad guys and evidently is untroubled by his own criminal behavior. He tells Harry a story about his saving the life of a junkie who shortly thereafter killed an old woman while robbing her, concluding,

That’s what’s wrong with this fucking hole of a country, no one gives a fuck, someone else’ll take care of it. Then the shit comes down and you come looking to me, expecting me to give a fuck. Well, I give a fuck, Rigby. Fuck you, that’s the fuck I give. I’m ten years in this gig, haven’t moved up since the junkie offed the granny. Galway’s job’ll pay the bills and a whole lot more besides. All you give me is a pain in the hole. (EBB 238)Burke’s two Harry Rigby books push the hardboiled to its limits, taking every familiar convention to its logical extreme endpoint. The violence that is so much a part of the American hardboiled manifests in Burke’s series as extreme violence, often beyond what even Mickey Spillane concocted. Harry is the target of much of that violence, but he also metes it out in ways that seem only tenuously related to hardboiled ideology. His violence is more akin to a sort of frenzied, hopeless vengeance. Burke’s detective does not prove his own superior toughness through enduring and dispensing violent assaults; instead, he demonstrates his own impotence. Indeed, Slaughter’s Hound ends with Harry evidently bleeding to death, away from any possible help. In a 2013 interview, Burke asserted that he wanted the series to employ the “classic tropes of 1930s stuff” in an Irish setting; this ending seems far away indeed from the classic hardboiled ending.

The reality is that, as the Rigby books inadvertently illustrate, those tropes cannot simply be transplanted and then operate precisely the same way in their new Irish context as they did in their old American one. Instead, the new context alters how those tropes—corrupt authority conspiring with the wealthy to subvert the law, dangerous women, greed, violence, a romantic solitary investigator committed to his own ideal of justice and so on—may be deployed, and therefore fundamentally changes what they mean. The detectives in the American hardboiled often prevail against a specific criminal while recognizing both that damage done cannot be undone and that the particular case or cases they have resolved make little difference in the bigger scheme of things, which continues along a crooked path despite their efforts. But the American hardboiled is also imbued with a sense of something worth saving in the American national story, and as a whole, the novels of Chandler, Hammett, and similar writers suggests that the struggle against the forces of evil is not hopeless. In contrast, the two Rigby books suggest that the Irish national situation is hopeless and that anyone who tries to put things right is destined for destruction. Among the many ways that Burke pushes the boundaries of the hardboiled is by endangering the detective’s own child, Ben, who is in fact killed late in Slaughter’s Hound when Harry is driven off the road by a man he has believed to be dead. Ben’s death emphasizes that bleakness, serving as a warning about the fate of innocents in the new Ireland: there is no future for them there at all.

These contradictions in the Irish hardboiled help to explain why most of the series stall out. The lives and attitudes of the Irish detectives become bleaker and bleaker, with everything eventually stripped away. Their loved ones, including children, die senseless deaths in most of these series—a fate the American hard-boiled avoided by not allowing the detectives any loved ones. There is no place for the detectives, or their series, to go. Benjamin Black may choose to keep the Quirke series alive, as it is lodged in the past—but it is hard to see what he might find worth saving in the Irishness the series has depicted as irredeemable. Ken Bruen has continued to write beyond the logical ending of the Jack Taylor series in Sanctuary. But Bruen project has devolved, in the later books. into an outright attack on everything Irish: gone are the earlier books’ attempts at redefinition, at scuttling the corrupt institutions, but holding out the possibility that the new Irishness might be more inclusive and less harshly judgmental than its bygone variants. Indeed, the devil himself appears in Ireland in a late Bruen novel and no one but Jack Taylor seems to notice: in Bruen’s universe, Satan is not much worse than everyone else and fits right in to Irish society. In the Irish hardboiled thus far, redefining Irishness proves to be impossible. It remains an empty category, and will continue to be in this genre until the Irish writers forswear their fealty to the American hardboiled.

This paper was first published in the New Hibernia Review ©

Thursday, November 26, 2015

News: Jane Casey’s AFTER THE FIRE Wins the Irish Crime Novel of the Year

“The latest in Jane Casey’s excellent series of police procedurals, After the Fire (Ebury Press, £12.99) sees DC Maeve Kerrigan and her colleagues investigate the aftermath of a fire on the top floors of Murchison House, a 1970s tower block in the Maudling council estate … Casey writes with a deft wit and immense skill … The Maeve Kerrigan books keep getting better and better.”

Saturday, October 3, 2015

Launch: John Connolly and Brian McGilloway at No Alibis

Meanwhile, Brian McGilloway has just published the third in his Lucy Black series, PRESERVE THE DEAD (Corsair), with the blurb elves wittering thusly:

Detective Sergeant Lucy Black is visiting her father, a patient in a secure unit in Gransha Hospital on the banks of the River Foyle. He’s been hurt badly in an altercation with another patient, and Lucy is shocked to discover him chained to the bed for safety. But she barely has time to take it all in, before an orderly raises the alarm - a body has been spotted floating in the river below...Writing in last weekend’s Irish Times, Declan Hughes was very impressed indeed with PRESERVE THE DEAD. For the full review, clickety-click here …

The body of an elderly man in a grey suit is hauled ashore: he is cold dead. He has been dead for several days. In fact a closer examination reveals that he has already been embalmed. A full scale investigation is launched - could this really be the suicide they at first assumed, or is this some kind of sick joke?

Troubled and exhausted, Lucy goes back to her father’s shell of a house to get some sleep; but there’ll be no rest for her tonight. She’s barely in the front door when a neighbour knocks, in total distress - his wife’s sister has turned up badly beaten. Can she help?

In PRESERVE THE DEAD, Brian McGilloway weaves a pacy, intricate plot, full of tension to the very last page.

John and Brian co-launch their books at No Alibis in Belfast later this month, with the details as follows:

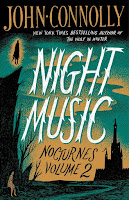

No Alibis is pleased (very, very pleased!) to invite you to our store on Thursday 22nd October at 7pm for the Double Launch Party of John Connolly and Brian McGilloway’s latest works, NIGHT MUSIC: NOCTURNES VOLUME 2 and PRESERVE THE DEAD.

We will also be celebrating the launch of our 4th limited edition publication. We are running a limited printing of NIGHT MUSIC: NOCTURNES VOLUME 2 by John Connolly. This edition is limited to 125 specially bound and slipcased copies, including exclusive artwork commissioned by Anne M. Anderson.

This incredibly special event will be sponsored by Boundary Brewing Company. An event not be missed, folks!

Friday, May 15, 2015

Interview: Dennis Lehane, author of WORLD GONE BY

Dennis Lehane is rightly regarded as one America’s great contemporary novelists. His debut novel, A Drink Before The War (1994), featuring the private eye duo Patrick Kenzie and Angie Gennaro, was the result, he says, of his being “obsessed with writing about the haves and the have-nots. Mainly the have-nots. I’m obsessed with that battle, if you will, that cultural war. And the place which seemed like a welcome home for those types of obsessions about violence and the social questions, the ills of our time, was crime fiction.For the rest of the interview, clickety-click here …

“I wrote A Drink Before The War so fast that part of me said, ‘Wow, you’ve got a comfort level here that you do not have when you’re trying to write much more overtly literary fiction.’ And then,” he laughs, “I went back to writing overtly literary fiction. But I was thinking more and more about crime fiction, and the next thing I wanted to say, and that became Darkness, Take My Hand [1996]. So that’s why I write these stories – it was a way to write about the things that fascinated me the most in our culture, and the crime fiction genre seemed to be tailor-made.”

Dennis Lehane will be in conversation with Declan Hughes at the Irish Writers’ Centre on May 28th.

Dennis will also appear at the Listowel Writers’ Festival on May 29th.

Wednesday, April 22, 2015

Launch: THE ORGANISED CRIMINAL by Jarlath Gregory

Spiked with black humour throughout, The Organised Criminal introduces us to Jay O’Reilly reluctantly returning to his family home. A childhood steeped in dysfunction with his family of criminals made him determined never to return, despite his attempts to leave the past behind, comes home to bid a final farewell to his recently-departed cousin Duncan. Though Jay likes to think he’s turned his back on his community, his lost past still holds a bleak fascination for him. His father, a well-known smuggler in the city with a wealthy, far-reaching empire, comes to him with a proposal. As Jay contemplates the job offer he reacquaints himself with the place and the family he left, only to find that it is exactly as hard, cold and unwelcoming as he remembered. With the anxieties and troubles of Northern Ireland as a back drop, Jay’s story becomes one of fear, family ties and self-worth. When the truth behind his father’s offer is finally revealed, Jay faces the primal struggle between familial bonds and moral obligations.For more on Jarlath Gregory, clickety-click here …

Wednesday, March 18, 2015

Festival: Mountains to Sea

Wednesday March 18thFor all the details, including how to book your tickets, clickety-click here …

Jilly Leovy, Ghettoside

In conversation with Declan Hughes

Jilly Leovy’s Ghettoside is true crime like you never heard before, leaving all the crime thrillers and blockbuster TV series for dead, which is how a frightening number of young black Angeleno males end up. Based on a decade embedded with the homicide units of the LAPD, this gripping, immersive work of reportage takes the reader onto the streets and into the lives of a community wracked by a homicide epidemic. Ghettoside provides urgent insights into the origins of such violence, explodes the myths surrounding policing and race, and shows that the only way to fight the epidemic successfully is with justice.

Post-Ferguson, this is the book you have to read to understand the issue of policing black neighbourhoods. Jill Leovy has been a reporter for the LA Times for 20 years, and has been embedded with the LAPD homicide squad on and off since 2002. In 2007 she masterminded and wrote the groundbreaking Homicide Report for the LA Times, ‘an extraordinary blog’ (New Yorker) that documented every one of the 845 murders that took place in LA County that year.

Local author Declan Hughes is well known to festival audiences. Hailed as ‘the best Irish crime novelist of his generation’, his latest novel is All the Things You Are.

Venue: dlr Lexicon / Time: 6.30pm / €10/€8 Concession

Friday March 20th

SJ Watson & Paula Hawkins

Chaired by Sinéad Crowley

How well do we know our family, our closest friends? How well do we really know ourselves? S.J. Watson’s new novel, Second Life, explores identity, lies and secrets in a nail-biting new psychological thriller. Watson’s debut novel, Before I Go To Sleep, became a phenomenal international success. It has now sold over 4 million copies around the world and has been made into a hit Hollywood film starring Colin Firth and Nicole Kidman.

Paula Hawkins’ The Girl on the Train has become a publishing sensation before it has even hit the shops with early reviewers anointing it as “the new Gone Girl”. The central conceit is brilliant. Rachel catches the same commuter train every morning. Each time it waits at the same signal, overlooking a row of houses. And then she sees something shocking. It’s only a minute until the train moves on, but now everything’s changed.

Sinéad Crowley is Arts & Media correspondent with RTÉ News. Her debut thriller Can Anybody Help Me? was published in 2014.

Venue: Pavilion Theatre / Time: 6.30pm / €10/€8 Concession

Tuesday, March 17, 2015

Overview: The St Patrick’s Day Rewind

An interview with Tana French on the publication of BROKEN HARBOURFor updates on the latest on all Irish crime writers, just type the author’s name into the search box at the top left of the blog …

In short, Tana French is one of modern Ireland’s great novelists. Broken Harbour isn’t just a wonderful mystery novel, it’s also the era-defining post-Celtic Tiger novel the Irish literati have been crying out for.

An interview with Alan Glynn on the publication of WINTERLAND

“I think that the stuff you ingest as a teenager is the stuff that sticks with you for life,” says Glynn. “When I was a teenager in the 1970s, the biggest influence was movies, and especially the conspiracy thrillers. What they call the ‘paranoid style’ in America – Klute, The Parallax View, All the President’s Men, Three Days of the Condor, and of course, the great Chinatown … We’re all paranoid now.”

A triptych of reviews of John Connolly’s THE LOVERS, Stuart Neville’s THE TWELVE (aka THE GHOSTS OF BELFAST) and Declan Hughes’ ALL THE DEAD VOICES:

“But then The Lovers, for all that it appears to be an unconventional but genre-friendly take on the classic private eye story, eventually reveals itself to be a rather complex novel, and one that is deliciously ambitious in its exploration of the meanings behind big small words such as love, family, duty and blood.”

“Whether or not Fegan and his ghosts come in time to be seen as a metaphor for Northern Ireland itself, as it internalises and represses its response to its sundering conflicts, remains to be seen. For now, The Twelve is a superb thriller, and one of the first great post-Troubles novels to emerge from Northern Ireland.”

“As with Gene Kerrigan’s recent Dark Times in the City, and Alan Glynn’s forthcoming Winterland, Hughes’s novel subtly explores the extent to which, in Ireland, the supposedly exclusive worlds of crime, business and politics can very often be fluid concepts capable of overlap and lucrative cross-pollination, a place where the fingers that once fumbled in greasy tills are now twitching on triggers.”

A review of Eoin McNamee’s ORCHID BLUE

“Students of Irish history will know that Robert McGladdery was the last man to be hanged on Irish soil, a fact that infuses Orchid Blue with a noir-ish sense of fatalism and the inevitability of retribution. That retribution and State-sanctioned revenge are no kind of justice is one of McNamee’s themes here, however, and while the story is strained through an unmistakably noir filter, McNamee couches the tale in a form that is ancient and classical, with McGladdery pursued by Fate and its Furies and Justice Curran a shadowy Thanatos overseeing all.”

A review of Jane Casey’s THE LAST GIRL

On the evidence of THE BURNING and THE LAST GIRL, Maeve Kerrigan seems to me to be an unusually realistic and pragmatic character in the world of genre fiction: competent and skilled, yet riddled with self-doubt and a lack of confidence, she seems to fully inhabit the page. This was a pacy and yet thoughtful read, psychologically acute and fascinating in terms of Maeve’s personal development, particularly in terms of her empathy with the victims of crime.

Eoin Colfer on Ken Bruen’s THE GUARDS

“I was expecting standard private-investigator fare, laced with laconic humour, which would have been fine, but what I got was sheer dark poetry.”

A review of Adrian McKinty’s THE COLD COLD GROUND

As for the style, McKinty quickly establishes and maintains a pacy narrative, but he does a sight more too. McKinty brings a quality of muscular poetry to his prose, and the opening paragraph quoted above is as good an example as any. He belongs in a select group of crime writers, those you would read for the quality of their prose alone: James Lee Burke, John Connolly, Eoin McNamee, David Peace, James Ellroy.

Tuesday, February 3, 2015

Event: ‘Northern Noir’ in Coleraine with Brian McGilloway

Libraries NI has put together a strong line-up of authors events for the coming weeks creating that personal connection for the public to meet popular writers which they admire and appreciate.A few of the highlights:

Libraries NI has programmed the ‘NI Author Collection’ showcasing home-grown talent and for lovers of crime fiction the ‘Catch a Crime Writer’ series will be running in mid-February. The up and coming events are listed below.

This is an occasion to find out what’s behind the story, why it was written, how the artistic, creative and psychological process developed? The aim of these events is to inspire the public to read more and consider novels which they would never have read before. Libraries NI trust that people will be encouraged to visit their local library or even visit a new one and meet a favourite author. It’s a real opportunity to discover what inspires writers, hear their fascinating stories or simply get a preview of the author’s latest book, sprinkled with a little author charm!

Wednesday 11th February at 7:30pmThe programme also includes Anne Cleeves, Michael Ridpath and Louise Phillips. For all the details, clickety-click here …

Coleraine Library

‘Northern Noir’, hosted by Brian McGilloway, and including Eoin McNamee, Stuart Neville and Steve Cavanagh

Thursday 26th February at 6:45pm

Belfast Central Library

An audience with Declan Hughes

Saturday, January 10, 2015

News: Irish Crime Fiction at Trinity College

“‘The detective novel’, wrote Walter Benjamin, ‘has become an instrument of social criticism’. This new co-taught seminar will explore perhaps the fastest-growing area of contemporary Irish literature, the Irish crime novel, considering its roots, its emphasis on crisis and change in a society, and its ability to distil and magnify a society’s obsessions. For these reasons, studies of Irish crime fiction are on the cusp of becoming a key strand in the study of contemporary Irish culture, here and abroad.”Authors under scrutiny include John Connolly, Declan Hughes, Tana French, Arlene Hunt, Benjamin Black, Eoin McNamee and Stuart Neville, with DOWN THESE GREEN STREETS playing its humble part as one of the establishing texts.

For more, clickety-click here …

Wednesday, November 19, 2014

Event: Nordic Noir / Celtic Crime

Join us for a panel discussion with Scandinavian and Irish crime fiction writers for what’s likely to be the final Battle of Clontarf millennial celebrations. Our line-up includes Thomas Enger (Norway) and Arts and Media Correspondent with RTÉ news Sinéad Crowley (Ireland) and Leif Ekle, culture expert, freelance journalist and broadcaster with Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation, NRK.For all the details, clickety-click here …

Declan Hughes (Ireland) will chair the panel and up for discussion are the different processes in writing crime fiction and exploring how culture, geographical location and gender influence the process.

Free Event, suggested donation €5

Thursday, June 12, 2014

All Decs On Hand

Anyway, in the interests of adding to the confusion, I’ll be appearing with Declan Hughes at the Dalkey Book Festival next month. The gist, according to the good people at the DBF, runs thusly:

There has never been so much interest in Irish crime writing and we are thrilled to have two of the best here for you this year.The event takes place at The Masonic Hall at 12.30pm, Saturday 21st June. For all the details, including how to book tickets, clickety-click here …

In an event called ‘Emerald Noir’, two of Ireland’s best crime writers, Declan Hughes and Declan Burke, take you through their favourite writers and discuss their own books in the context of current Irish crime fiction.

Sunday, May 4, 2014

“Ya Wanna Do It Here Or Down The Station, Punk?” Lisa Alber

What crime novel would you most like to have written?

This may sound perverse, but I’d love to channel the darkness that burbles around inside Gillian Flynn. She’s wicked! Have you seen photos of her? Looks like she bakes pies for homeless people. Any of her novels will do: SHARP OBJECTS, DARK PLACES, or GONE GIRL.

What fictional character would you most like to have been?

Fictional characters go through too many hardships and conflicts before their happy endings. I’m too lazy for all that. There’s gotta be a sidekick out there who lives a charmed life and is only around enough to support the hero. That’s more my speed. Anyone got any ideas for me?

Who do you read for guilty pleasures?

DA VINCI CODE-type thrillers are my guilty pleasures because I love all that Catholic Church conspiracy stuff. I also like pseudo-scientific symbology stuff that incorporates our greatest myths into the story lines. I just finished a thriller centred around the Amazons. Fun stuff.

Most satisfying writing moment?

The “a-ha.” You know when you’re writing along, maybe it’s not going well, but you’re slapping down the words anyhow (knowing you’ll have a helluva rewrite later), and then somehow, you lose sense of yourself and time and the world around you, and then later you come to and an hour has passed and you can’t remember what you wrote exactly, but you know it’s something grand? Yeah, that. That’s what I love. It’s rare, but the potential is always there. Also, the a-ha moment when you’re writing along and all of a sudden a fantastic idea comes to you out of nowhere -- a plot twist or character revelation -- and you feel so euphoric, the best high ever, that you jump out of your chair and do a little jig that causes your cat to tear out of the room? Yeah, that too.

If you could recommend one Irish crime novel, what would it be?

I’m still in Irish-crime-novel discovery mode! Some of the obvious recommendations for people like me who aren’t as well-read as they could be are Tana French and Benjamin Black (a.k.a. John Banville) – and you too. Immediate curiosity has me leaning toward checking out Arlene Hunt, Adrian McKinty, Declan Hughes, and Bartholomew Gill (although he’s Irish-American) next.

What Irish crime novel would make a great movie?

Benjamin Black’s first mystery, CHRISTINE FALLS, would make a fabulous movie. I picture something stylized, gritty, atmospheric, and filmed in a limited palette (neo-noir Mulholland Drive comes to mind). The way the central mystery about dead Christine slowly circles in on the starring detective’s family baggage is great. Plus, it’s got Catholic Church stuff in it. Like I said above, I can’t get enough of that.

Worst / best thing about being a writer?

Right now, the worst thing about being a novelist is my need for a day J-O-B. It’s a creative energy sucker, that’s for sure. I struggle to find energy to get the fiction writing in--before work, after work, on weekends. I’m the kind of person who needs long swaths of down time to stay centred and to rejuvenate. The best things are the ‘a-ha’ moments I described above.

The pitch for your next book is ...?

My debut novel, KILMOON, just came out. It’s set in County Clare, the first in a series.

“Family secrets, betrayal, and vengeance from beyond the grave … Merrit Chase is about to meet her long-lost father. Californian Merrit Chase travels to Ireland to meet her father, a celebrated matchmaker, in hopes that she can mend her troubled past. Instead, her arrival triggers a rising tide of violence, and Merrit finds herself both suspect and victim, accomplice and pawn, in a manipulative game that began thirty years previously. When she discovers that the matchmaker’s treacherous past is at the heart of the chaos, she must decide how far she will go to save him from himself—and to get what she wants, a family.”

I’m working on the second novel in the series, for the moment called Grey Man. Things get personal, oh so personal, when a teenage boy dies and disaster hits Detective Sergeant Danny Ahern’s family as a result.

Who are you reading right now?

I’m trying out an author I’ve never read before: James Barney, THE JOSHUA STONE. Another in the realm of guilty pleasures because it features secret government experiments and voodoo science.

God appears and says you can only write OR read. Which would it be?

I could give up writing if I had to (it’s freaking hard work!), but never reading. Reading goes along with those long swaths of down time I require.

The three best words to describe your own writing are ...?

Atmospheric, multi-layered, and intricate.

KILMOON is Lisa Alber’s debut novel.